This is an excerpt of a post originally published at rainmakerenterprise.org as an update on progress to date on the Tonj Solar Irrigation Project which is partially supported through the Network’s Rainmaker Affiliate community. All photos: Jean Luc Habimana

After months of remote planning between Canada and South Sudan, Rainmaker finally reached Tonj early this spring to continue planning face-to-face. Thanks to support from the Humanitarian Grand Challenge, there is cause for great excitement as our dream to restore hope through community-driven approaches in conflict-affected zones is finally becoming a reality.

We’re excited to share updates from South Sudan in preparation for our proof-of-concept project in Tonj.

COMMUNITY CO-DESIGN

The co-design process is key for understanding the challenges and barriers people are facing in a fast-changing environment. Co-designing interventions with our partner communities enables us to establish strong partnerships and ensure sustainability. We sat down with respected elders, community members and authorities to develop plans and address concerns. Ensuring people’s voices are broadly heard and respected is central to our project’s success.

WHAT WE LEARNED

Lack of access to safe and clean water is a major challenge crippling economic, social and environmental development across South Sudan. People are facing neglected or destroyed water infrastructure, with up to 80% of the country’s population currently lacking access to water, according to the government water authority. There is a lack of reliable water source in the communities surrounding our project site, with the dry seasons getting longer, causing failed harvests and clashes between communities over scarce resources. People must walk long distances to collect water from old pumps or open sources with worn containers. This task falls on women and youth, leaving them vulnerable to attacks and keeping children – especially girls – out of school. Lack of water is driving poverty, health challenges, and food insecurity in our communities.

For pastoralists who depend on access to water and grazing pastures for their cattle, this photo presents a grim picture of the hardships people face to keep their livestock nourished. This year, families lost hundreds of livestock to starvation and dehydration from the extreme dry conditions. Pastoralists are forced to move further and communities are increasingly pitted against each other over the limited water sources, causing forced migrations and further loss of property.

Traditional mechanisms have historically contained and managed these clashes, but dwindling water resources combined with the broader conflict are straining these solutions. Pastoralism provides the main source of income and food for the majority of the country’s population, with over 70 percent of people participating in the pastoral economy. Secure and inter-communally managed resources are key for South Sudan’s lasting peace and development.

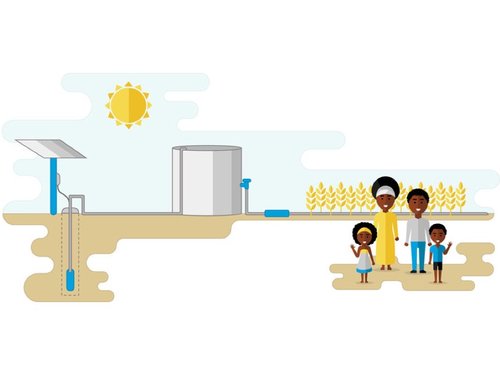

BEYOND WATER AND SANITATION: SOLAR-POWERED WATER PUMPS FOR REGENERATIVE AGRICULTURE

The transformational potential of water hinges on infrastructure that can deliver not only for household consumption, but also for livelihood needs, including agriculture and livestock-raising. People shared with us the limitations of the handpumps that have long served rural Africa. We identified the need to install a solar-powered water pump between the two constituencies of Alorweng and Angol in Thiet County, Tonj State. This will feed two water kiosks with tap systems, delivering water to each community through an inter-communally managed distribution system. The water source will also be connected to a water-efficient drip irrigated farm, where we will train and employ the local population on sustainable farming techniques. We aim to provide economic empowerment for women and youth while producing year-round crops, beginning with the groundnut crop, to improve food security and nutrition levels. Our farming approach involves intercropping fruit-bearing trees on the farmland to contain encroaching desertification.

LAND ACQUISITION AND REGISTRATION

Our pilot site sits on over 40 acres of fertile and secure land. We settled on the location based on fertility of the land, sufficient groundwater resources, security and steady community relations, and the location of greatest need. Luckily South Sudan is blessed with ample fertile land. Recognizing the importance of sustainable use of South Sudan’s ample fertile land and agriculture for the country’s recovery and development, local and regional authorities were receptive to our proposal. Broad-based negotiations, including traditional and non-traditional authorities and community members, were aimed at ensuring the project will be a source of cooperation from the beginning and that our agreement remains secure for the communities the project serves. We are thrilled to have secured over 40 acres of land for our pilot.